» Mitgliedschaft

» Öffentlichkeitsarbeit

» Angebote für Schulen

» Satzung

» Umsetzung DSGVO

» Archivnutzung

» Kontakt

» Unterstützen

English Sites

» History of the DOG» Structure and Aims

The Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft was founded in 1898 in Berlin with the aim of promoting research in the field of Oriental archaeology and bringing it to a wider audience. The historical backdrop to this had formed in the second half of the 19th century through a marked growth in the general public's interest in the "Bible lands", where in particular the French and the English were making spectacular discoveries.

|

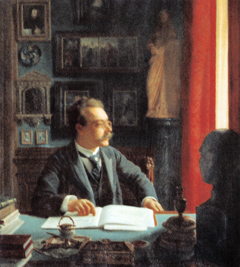

| James Simon, Founder and Patron of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft |

It was seen as a major shortcoming in Berlin at the end of the nineteenth century that Germany still lacked a museum that could boast a sizeable collection of ancient Near Eastern art, of the kind that the British Museum and the Louvre long since owned. So initially a considerable part of the work of the DOG consisted in supporting the efforts of the Königliche Museen zu Berlin to acquire oriental antiquities and monuments of art and culture.

One of the founding fathers of the DOG was the Berlin textile wholesaler, art lover and patron James Simon. Thanks to his connections with commerce, banking and industry, a large number of well-known and well-off members of society soon became members of the DOG, which allowed it to undertake excavations in the Orient at its own cost. With its explorations in Babylon a sizeable undertaking was immediately set in motion. From 1898 to 1917 the dig in Babylon under the direction of Robert Koldewey uncovered such important constructions as the Processional Way and the Ishtar Gate now on view in the Museum of the Ancient Near East, as well as the palaces of Nebuchadnezzar and the famous Tower of Babel.

|

| Babylon, beginning of work on the Ishtar Gate, © DOG |

In 1901 Kaiser Wilhelm II, who took an inordinate interest in archaeology, assumed the patronage of the DOG, which resulted in generous endowments from the imperial coffers. But apart from this, subsidies from the Prussian State Government and generous donations also helped place the society's wide range of ventures on a solid financial basis.

As an offshoot of the Babylonian Expedition, further explorations were performed in 1902-1903 in Borsippa, where the remains of a tower-shaped ziggurat still commanded the scene far and wide, and in Fara, once known as Shuruppak. According to cuneiform texts that have been handed down to us, Fara was the home of the flood hero Utnapishtim, the equivalent of Noah in the Bible. The excavations revealed the floor plans of houses from the 3rd century BCE together with rich inventories of finds, including archives of clay tablets.

|

| Abusir el-Meleq, prehistoric make-up dish, © Egyptian Museum Berlin / M. Büsing |

|

| Hattusa, two deities from the netherworld, carved in the rock sanctuary of Yazilikaya, © Prof. Dr. Gernot Wilhelm |

The DOG was quick to extend its activities to Egypt. From 1902 onward it funded the work of Ludwig Borchardt on a 5th dynasty pyramid field at Abusir. This was followed some years later by the excavation of a predynastic cemetery in Abusir el-Meleq. The climax and provisional end of the DOG's work in Egypt was the archaeological dig from 1911 to 1914 in Tell el-Amarna, the capital of the Pharaonic empire that was founded from scratch in the 18th dynasty under Echnaton. This led to the uncovering of the workshop run by the sculptor Thutmose, from which the famous bust of Queen Nefertiti hailed.

Between 1903 and 1909 the DOG also sponsored archaeological explorations in Palestine. This was followed by its financial involvement in the excavations at Megiddo and Tell es-Sultan, the Biblical Jericho, and in a study of the ruins of Galilean synagogues.

In Asia Minor the DOG backed the excavations that Hugo Winckler and Theodor Makridi embarked on in 1906 in the Hittite capital of Hattusa. Right from the outset, its collaborations with the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut reaped rich finds in the realms of architecture, sculpture and tablets.